Dear Little Daughter (Part 4)

If you missed Part Three, click HERE.

I had quit my job. Now what?

It was April 1995. Following a brief trip to visit my parents in Arizona, I spent my mornings sitting on the ground in the backyard of our little house, breaking up freshly cut soil by crumbling it between my fingers to create the bed for a vegetable garden.

Bathed by the sun’s warmth and in a nearly meditative state, I contemplated what I had learned so far about the people in the box, and what I was learning about myself—how following their stories, like planting a garden, seemed to nourish my soul.

I called Millie Ladner, the one Lillian Norberg told me was Elizabeth’s “fastest friend.”

From Millie, I learned that Elizabeth’s death was unexpected and that her husband, Dr. James Thompson, was so heartbroken that he sold the house soon thereafter and moved to be nearer his son, Jimmy.

From Millie, I learned that Elizabeth’s death was unexpected and that her husband, Dr. James Thompson, was so heartbroken that he sold the house soon thereafter and moved to be nearer his son, Jimmy.

Millie did not have an address or telephone number for the Doctor or Jimmy, but she was also adamant that I find Elizabeth’s daughter, Patty. The only trouble was … she didn’t know where Patty was, either.

Before our call ended, I also learned more about Millie herself.

She was one of the first female reporters for the Associated Press and the only female reporter with the Wall Street Journal when they hired her for their Washington Bureau in 1945. She wrote under the name ‘M. M. Diefenderfer’ so the newspaper could retain credibility with its male readership.

Among other important stories, she was one of the few reporters to witness and cover the first and only flight of the Spruce Goose (Hughes H-4 Hercules), the prototype aircraft created by Howard Hughes. On a more lighthearted note, while covering the Truman Administration, she learned to put lipstick on without the benefit of a compact mirror in the Press Briefing Room at the White House.

Among other important stories, she was one of the few reporters to witness and cover the first and only flight of the Spruce Goose (Hughes H-4 Hercules), the prototype aircraft created by Howard Hughes. On a more lighthearted note, while covering the Truman Administration, she learned to put lipstick on without the benefit of a compact mirror in the Press Briefing Room at the White House.

There were so many stories.

The box had already shared so much with us about Elizabeth and her ancestors, and now, like branches on a tree, it was sprouting more stories about others in her life.

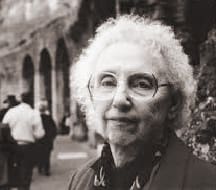

Millie gave me the names of more friends from their Tulsa group that she thought I should contact, including Evelyn Bachmann.

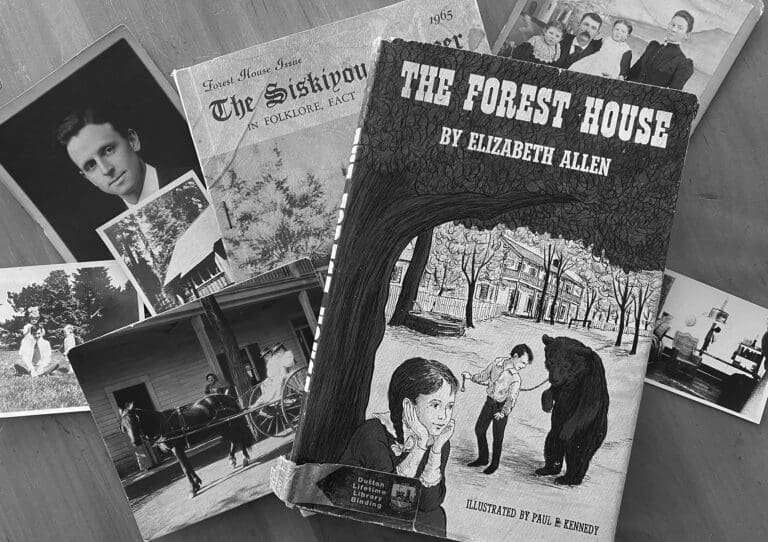

Evelyn was a local poet and author who, according to Millie, had shared the writing of her daughter’s high school friend, Susie Hinton, with Elizabeth in 1965.

I discovered Evelyn lived just a few miles from us and almost directly across from The University of Tulsa, where Michael and I earned our college degrees—his in Television Production, mine in Journalism.

I discovered Evelyn lived just a few miles from us and almost directly across from The University of Tulsa, where Michael and I earned our college degrees—his in Television Production, mine in Journalism.

I called her, and that very afternoon, I found myself seated at Evelyn’s kitchen table, sharing the contents of the box.

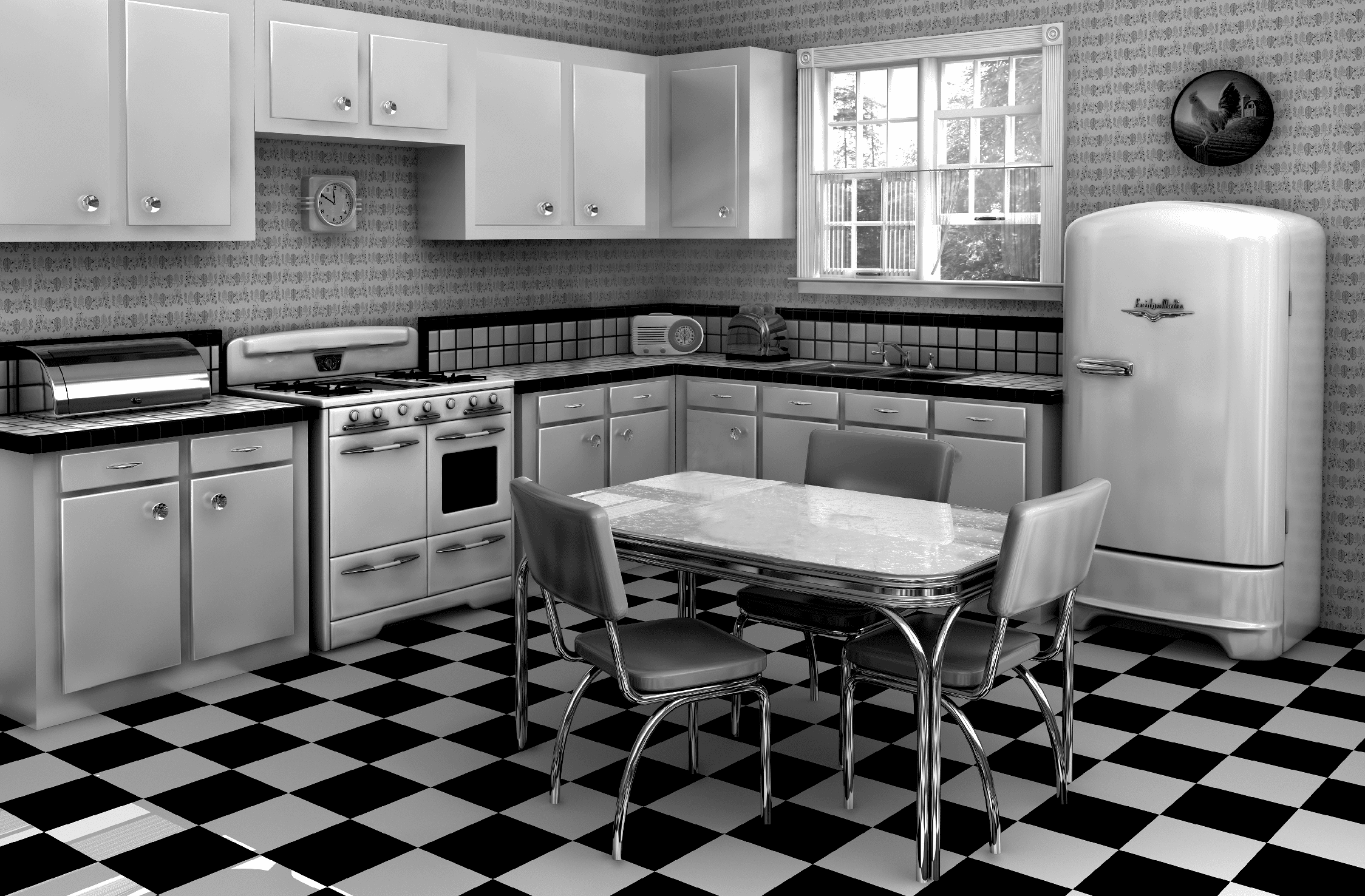

It was as if I had been transported back in time. Evelyn’s kitchen was distinct from her cozy living room, a charming departure from the seamless spaces of modern homes. Its marbled Formica-topped table was trimmed in shiny aluminum and had matching chairs. The set complemented the kitchen’s countertops. The whole thing screamed the 1950s.

Like my friend Kendra and everyone else we had talked to, Evelyn was amazed by the box’s contents and wondered aloud about how it could have ended up outside of the family’s possession. She wished she knew how to reach Patty or Jimmy, but she didn’t.

I asked her about Susie Hinton, better known as S. E. Hinton, author of The Outsiders and other young adult novels.

Evelyn said her daughter, Donna, attended Will Rogers High School with Susie. Donna had shared Susie’s writing with Evelyn and Evelyn, in turn, shared it with Elizabeth.

She laughed as she recalled Elizabeth’s response.

“Oh, Evelyn, Don’t you just hate her? Her writing is sooo good!”

Knowing Susie had natural talent, Elizabeth contacted her New York publisher and, in doing so, helped launch the young author’s career.

I also shared with Evelyn how much I loved poetry.

I also shared with Evelyn how much I loved poetry.

“Who is your favorite,” she asked.

“Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,” I said without hesitation.

“Psalm of Life?” she challenged.

“Psalm of Life,” I nodded in response.

Then, still seated at her kitchen table, we spontaneously and robustly recited it aloud—together.

Psalm of Life

What The Heart Of The Young Man Said To The Psalmist.

Tell me not, in mournful numbers, life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers and things are not what they seem.Life is real! Life is earnest! And the grave is not its goal.

Dust thou art, to dust returnest, was not spoken of the soul.Not enjoyment, and not sorrow, is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow find us farther than to-day.Art is long, and Time is fleeting, and our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating funeral marches to the grave.In the world’s broad field of battle, in the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle! Be a hero in the strife!Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant! Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,—act in the living Present! Heart within, and God overhead!Lives of great men all remind us we can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us footprints on the sands of time;Footprints, that perhaps another, sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother, seeing, shall take heart again.Let us, then, be up and doing, with a heart for any fate;

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, 1838. WRITTEN AFTER HIS FIRST WIFE’S DEATH AS HE CONTEMPLATED HOW TO MOVE FORWARD.

Still achieving, still pursuing, learn to labor and to wait.

What a joy to recite this beautiful poem with my newfound 76-year-old friend, for it meant even more to me now. Like the forlorn and shipwrecked brother of Longfellow’s poem, I had taken heart in the footprints left behind by the people in the box and the path they put before me.

It was a magical afternoon and a moment that will live in me to the end of my days.

Read the next segment of this story in Part Five.